2

Followers

6

Following

Lucy's Books

Old enough to be reading fairy tales again, and reading lots more for good measure.

I might have read this book much sooner if I hadn't been unfairly prejudiced against it since Mrs. Hodges' tenth grade English class. Most people have a story where the teaching of literature ended up running counter to their enjoyment of it; luckily, mine is confined to one year of high school. For some reason, rather than read whole works, our class was assigned to read several single chapters excerpted from Great Books, including Lord of the Flies, Les Miserables, and The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. This is a terrible teaching method, leaving out all the context, development, and nuance; in the case of this book, my impression was that it consisted of terse, cold writing, flat characters, and dull themes. Ironically perhaps, these are all opposite impressions gathered from reading the book in full as it was meant to be read. This is a remarkable book, perhaps the best I've read this year.

I might have read this book much sooner if I hadn't been unfairly prejudiced against it since Mrs. Hodges' tenth grade English class. Most people have a story where the teaching of literature ended up running counter to their enjoyment of it; luckily, mine is confined to one year of high school. For some reason, rather than read whole works, our class was assigned to read several single chapters excerpted from Great Books, including Lord of the Flies, Les Miserables, and The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. This is a terrible teaching method, leaving out all the context, development, and nuance; in the case of this book, my impression was that it consisted of terse, cold writing, flat characters, and dull themes. Ironically perhaps, these are all opposite impressions gathered from reading the book in full as it was meant to be read. This is a remarkable book, perhaps the best I've read this year.While I regret not reading McCullers' masterpiece sooner, I also think I may never have appreciated this book more than I do now. I am only 25 years old, barely outside adolescence, but at the same time teetering over the rim of that era of precociousness. Bruce Springsteen was just 25 when he exploded with Born to Run, but it won't be too long before I can quote whoever it was who pointed out, "At my age, Keats had already been dead for three years!" McCullers was a prodigy herself, publishing The Heart is a Lonely Hunter at only 23 years old. It's the kind of fact that makes my old dream of writing stories seem within reach, and at the same time recognize, I could never be this good. This is so good. This is perfect.

Readers say this is the story of John Singer, the town's deaf-mute whose pleasant demeanor and fair mind entrance other lonely misfits to confide and idolize the one person who can't talk to them, while he himself has only one true friend in an angry, sickened deaf mute named Antonapoulos. Or they say that it is the story of Mick, the tomboy teenager who can't stop hearing music and resembles McCullers autobiographically. But I was most drawn toward the story of bartender Biff Brannon, who watches and ponders and hopes to understand. He stands in for the writer, since as fellow writing prodigy David Foster Wallace points out in his essay "E Plurabus Unam: Television and U.S. Fiction", writers are born watchers. Biff who keeps the cafe open late despite there being no money in it, who is strangely drawn toward young Mick for reasons he can't put into words.

He examined the zinnia he had intended to save. As he held it in the palm of his hand to the light the flower was not such a curious specimen after all. Not worth saving. He plucked the soft, bright petals and the last one came out on love. But who? Who would he be loving now? No one person. Anybody decent who came in out of the street to sit for an hour and have a drink. But no one person. He had known his loves and they were over. Alice, Madeline and Gyp. Finished. Leaving him either better or worse. Which? However you looked at it.

Everyone in this book is lonely, from Jake the drunk communist mechanic, trying to change the world one "don't-know" at a time, to Doctor Copeland, a black doctor angry at the injustices against his people and also seeking change and reform, but seeing little hope in the future. If I had read this book much sooner, I wouldn't have understood this so well. I spent much of my life growing up very alone and isolated and numb to much of the world, living through stories and books and scientific facts without feeling much need for people. And then I loved someone and through understanding them, better understood myself, including a deep affection and appreciation for all people that had been buried under cynicism and a facade of misanthropy. This is a book that feels all of that, the love, loss, connection, and isolation. What seemed like emotionless prose to my tenth-grade eyes is actually some of the most sensitive, warmly quiet writing I've ever come across. It connects with the darkness and light within most people in plain, unornamental English, carefully astute observation, and a central fascination with that dilemma of dilemmas: each of us stands essentially alone, and yet, as Doctor Copeland says, this is also the most deadly thing a man can do. The twenty-something author provides a possible antidote to this paradox: we must try. Try to love, try to labor, and try not to be alone, though maybe we always will be. We have to keep trying.

1

1

There is a lovely passage toward the end of this book that I think encapsulates the whole.

There is a lovely passage toward the end of this book that I think encapsulates the whole."Now the final copper light of afternoon fades; now the street beyond the low maples and the low signboard is prepared and empty, framed by the study window like a stage.

He can remember how when he was young, after he first came to Jefferson from the seminary, how that fading copper light would seem almost audible, like a dying yellow fall of trumpets dying into an interval of silence and waiting, out of which they would presently come. Already, even before the falling horns had ceased, it would seem to him that he could hear the beginning thunder not yet louder than a whisper, a rumor, in the air.

But he had never told anyone that. Not even her. Not even her in the days when they were still the night’s lovers, and shame and division had not come and she knew and had not forgot with division and regret and then despair, why he would sit here at this window and wait for nightfall, for the instant of night. Not even to her, to woman. The woman. Woman (not the seminary, as he had once believed): the Passive and Anonymous whom God had created to be not alone the recipient and receptacle of the seed of his body but of his spirit too, which is truth or as near truth as he dare approach.

[...]

He remembers it now, sitting in the dark window in the quiet study, waiting for twilight to cease, for night and the galloping hooves. The copper light has completely gone now; the world hangs in a green suspension in color and texture like light through colored glass. Soon it will be time to begin to say Soon now. Now soon ‘I was eight then,’ he thinks. ‘It was raining.’ It seems to him that he can still smell the rain, the moist grieving of the October earth, and the musty yawn as the lid of the trunk went back. Then the garment, the neat folds. He did not know what it was, because at first he was almost overpowered by the evocation of his dead mother’s hands which lingered among the folds. Then it opened, tumbling slowly. To him, the child, it seemed unbelievably huge, as though made for a giant; as though merely from having been worn by one of them, the cloth itself had assumed the properties of those phantoms who loomed heroic and tremendous against a background of thunder and smoke and torn flags which now filled his waking and sleeping life.

The garment was almost unrecognisable with patches. Patches of leather, mansewn and crude, patches of Confederate grey weathered leafbrown now, and one that stopped his very heart: it was blue, dark blue; the blue of the United States. Looking at this patch, at the mute and anonymous cloth, the boy, the child born into the autumn of his mother’s and father’s lives, whose organs already required the unflagging care of a Swiss watch, would experience a kind of hushed and triumphant terror which left him a little sick.

[...]

He leans forward. Already he can feel the two instants about to touch: the one which is the sum of his life, which renews itself between each dark and dusk, and the suspended instant out of which the soon will presently begin. When he was younger, when his net was still too fine for waiting, at this moment he would sometimes trick himself and believe that he heard them before he knew that it was time.

[...]

In the lambent suspension of August into which night is about to fully come, it seems to engender and surround itself with a faint glow like a halo. The halo is full of faces. The faces are not shaped with suffering, not shaped with anything: not horror, pain, not even reproach. They are peaceful, as though they have escaped into an apotheosis; his own is among them. In fact, they all look a little alike, composite of all the faces which he has ever seen. But he can distinguish them one from another: his wife’s; townspeople, members of that congregation which denied him, which had met him at the station that day with eagerness and hunger; Byron Bunch’s; the woman with the child; and that of the man called Christmas. This face alone is not clear. It is confused more than any other, as though in the now peaceful throes of a more recent, a more inextricable, compositeness. Then he can see that it is two faces which seem to strive (but not of themselves striving or desiring it: he knows that, but because of the motion and desire of the wheel itself) in turn to free themselves one from the other, then fade and blend again. But he has seen now, the other face, the one that is not Christmas. ‘Why, it’s …’ he thinks. ‘I have seen it, recently … Why, it’s that … boy. With that black pistol, automatic they call them. The one who … into the kitchen where … killed, who fired the …’ Then it seems to him that some ultimate dammed flood within him breaks and rushes away. He seems to watch it, feeling himself losing contact with earth, lighter and lighter, emptying, floating. ‘I am dying,’ he thinks. ‘I should pray. I should try to pray.’ But he does not. He does not try. ‘With all air, all heaven, filled with the lost and unheeded crying of all the living who ever lived, wailing still like lost children among the cold and terrible stars. … I wanted so little. I asked so little. It would seem …’ The wheel turns on. It spins now, fading, without progress, as though turned by that final flood which had rushed out of him, leaving his body empty and lighter than a forgotten leaf and even more trivial than flotsam lying spent and still upon the window ledge which has no solidity beneath hands that have no weight; so that it can be now Now.

It is as though they had merely waited until he could find something to pant with, to be rearmed in triumph and desire with, with this last left of honor and pride and life. He hears above his heart the thunder increase, myriad and drumming. Like a long sighing of wind in trees it begins, then they sweep into sight, borne now upon a cloud of phantom dust. They rush past, forwardleaning in the saddles, with brandished arms, beneath whipping ribbons from slanted and eager lances; with tumult and soundless yelling they sweep past like a tide whose crest is jagged with the wild heads of horses and the brandished arms of men like the crater of the world in explosion. They rush past, are gone; the dust swirls skyward sucking, fades away into the night which has fully come. Yet, leaning forward in the window, his bandaged head huge and without depth upon the twin blobs of his hands upon the ledge, it seems to him that he still hears them: the wild bugles and the clashing sabres and the dying thunder of hooves."

This book just opens up my heart. It opened up my heart and poured itself in, a combination of magic and memory mixed into the most perfect concoction of semisolid cement filling that molded vessel.

This book just opens up my heart. It opened up my heart and poured itself in, a combination of magic and memory mixed into the most perfect concoction of semisolid cement filling that molded vessel.June is a lonely, introspective, imaginative girl. She loves her uncle Finn, who is dying of AIDS and who shows her the beautiful things in the world, like the medieval chambers of a New York cathedral or Mozart's Requiem. And after he dies, she folds up into herself, until she unravels some of the mysteries of who her uncle was beyond how she knew him, and finds someone who misses him as much as she did.

The Tom Waits song Time, sung beautifully by Tori Amos, haunts me as an appropriate soundtrack for much of this story. Two lonely characters in a windswept city, without forever ahead of them.

I can't recommend this book enough. Anyone should read it. I haven't recommended it that well, perhaps, but this review does awesome justice to a true contemporary beauty: http://www.goodreads.com/review/show/365322964

Craig Ferguson is a versatile and genial late-night talk show host. When I first became a fan of his show, what drew me in was his easy, friendly humor and genuine approach to interviews, preferring to engage in actual conversation over canned banter. He throws himself into goofy, off-the-wall sketches that display real originality and a lively, free style. His take on the late-night sidekick, for instance, takes the shape of a "Gay Robot Skeleton" named Geoff, designed by the team at MythBusters, for which he has professed avid fandom. He bleeps the profanity he or guests occasionally blurt out with cartoon flags accompanied by a sped-up "Tootsie Frootsie!" or another goofy quip.

Craig Ferguson is a versatile and genial late-night talk show host. When I first became a fan of his show, what drew me in was his easy, friendly humor and genuine approach to interviews, preferring to engage in actual conversation over canned banter. He throws himself into goofy, off-the-wall sketches that display real originality and a lively, free style. His take on the late-night sidekick, for instance, takes the shape of a "Gay Robot Skeleton" named Geoff, designed by the team at MythBusters, for which he has professed avid fandom. He bleeps the profanity he or guests occasionally blurt out with cartoon flags accompanied by a sped-up "Tootsie Frootsie!" or another goofy quip.

It wasn't until I'd already been reeled in by his charm that I came to understand there was a substantial depth within Mr. Ferguson. He writes in this book that he approaches his show with an effort towards honesty. In 2007 after Britney Spears had been in the news for some "crazy" antics, he performed a monologue that opened up about his past as an alcoholic, which meant that he couldn't help being compassionate towards her and disdainful of "attacks on the vulnerable". From that moment on, it was apparent that he had plenty of stories to tell.

The final step in the evolution of my understanding of Ferguson as a late night personality was his considerable intelligence and curiosity. Most comedians are bright and sharp, with a certain cleverness or astuteness about them that provides them insights into the everyday events most of us take for granted. But Craig displays a deep love of classic literature and humanistic inquiry, often playfully asking his guests whether they are more Jungian or Freudian. In 2009 he devoted an entire episode to an interview with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, for which he later received a Peabody Award. Having always been good at school and having been successfully educated, I am always fascinated by those who come to education in a more circuitous way, often with profound insights from their unique perspective and strong personal drive. It's admirable, and worth trying to learn from.

I spend all this time describing who Craig Ferguson is as a TV personality because once you know that, this book is a lot easier to understand and predict. It's a wise, open, funny take on his own life and the lessons that inform his path forward, framed by his choice to become an American citizen despite being Scottish-born. Listening to the audiobook was like listening to him tell a long story; heck, that's exactly what was. There were sections that were noticeably more spirited in their narration than others, and sections that described intricacies of certain showbiz choices that were probably more detailed than necessary. Like you would expect, he seems to have a stronger sense of the thread of narrative meaning intertwining the events in his distant past than the more recent ones, sometimes allowing those of the past few years to fall into a laundry list instead of a narrative. But for by far the greater part, it was a good story, and he's a friendly companion. At the beginning, he quotes William Blake, who said, "The road to excess leads to the palace of wisdom." It may not be a path that's fun to travel, but it certainly makes for a good yarn.

Fire Baton (Arkansas Poetry) (Arkansas Poetry Award)

I was thinking about Appalachian literature and this book, and realized that maybe the thing about Appalachian literature is that it's so much about the things that are gone, the empty spaces, the abandoned coal mines and lost futures and carved-out mountainsides. In a way, it can't help being haunted, metaphorically and, I think, sometimes literally - ghost stories sound perfectly set in some wafty mine shaft. In her poem "Ghosts for Dinner", Hadaway makes this connection on both levels:

I was thinking about Appalachian literature and this book, and realized that maybe the thing about Appalachian literature is that it's so much about the things that are gone, the empty spaces, the abandoned coal mines and lost futures and carved-out mountainsides. In a way, it can't help being haunted, metaphorically and, I think, sometimes literally - ghost stories sound perfectly set in some wafty mine shaft. In her poem "Ghosts for Dinner", Hadaway makes this connection on both levels:Get up to turn your chair away from her

a few degrees. And look at me. I may

be someone else's longed-for phantom. Pour

me some more wine; tell me the story; listen:

it's a dreary wish to want the whole globe ghostless.

It reminds me of something said about digital vs. analog film, that the split-second void between frames in traditional film projections engages the mind subconsciously and draws us into the experience further. Maybe that same quality captures our imagination here.

Hadaway's poems are written in the vulgate, everyday country language, about everyday country places, like the Magic City Mortgage Co, or the Kmart, or the hardware store. They're written about that tearing of leaving vs. staying, being "from here" or an outsider. Often, they are about choosing how to survive, "extermination or education" people are said to say. But at her heart, Hadaway says that her home is carried with her, as in the poem "Fancy Gap" about a mountain descent road that winds and curves dangerously:

When I left Fancy for that fellowship

in the far west, I thought it was the end

of her influence. She was passe, parsnip

abandoned in and old root cellar, wind

in rotten chestnut trees. [...]

And then I looked up from a restroom sink

at Fort Kearney, Nebraska, and I saw

my collarbone was Fancy's collarbone.

The mirror showed me with her tilted jaw,

my long brown hairs hers, gnarly and windblown

But at the same time, it's not so simple as that. Whether Hadaway has survived is not clear, whether she feels complete away from home undetermined. The exploration is beautifully made and rewarding to follow, in plain but elegant language, recalling her Virginia mountains homeland.

A Death In The Family (Turtleback School & Library Binding Edition)

A friend reintroduced me to [a:Theodore Roethke|7531|Theodore Roethke|http://d.gr-assets.com/authors/1238753648p2/7531.jpg] a few weeks ago. His poems have a raw, fiercely unintellectualized emotion, as here in the poem "In a Dark Time":

A friend reintroduced me to [a:Theodore Roethke|7531|Theodore Roethke|http://d.gr-assets.com/authors/1238753648p2/7531.jpg] a few weeks ago. His poems have a raw, fiercely unintellectualized emotion, as here in the poem "In a Dark Time":Dark, dark my light, and darker my desire.

My soul, like some heat-maddened summer fly,

Keeps buzzing at the sill. Which I is I?

A fallen man, I climb out of my fear.

The mind enters itself, and God the mind,

And one is One, free in the tearing wind.

I admire the artistry and I can tell that it is powerful; but it is often difficult for me to grasp or understand or conceptualize his ideas. Even the syntax hints at the problem -- it is meant to be felt, not thought about. And I can't always do that. So it remains a bit beyond me.

A Death in the Family has these same qualities. It is steeped in beautiful language and aching nostalgia for Agee's own remembrances of this place as both Knoxville, Tennessee and his childhood. His ability to inhabit the minds of children and various adults is remarkable. But the bulk of the story is the examination--no, the experience, of the emotional journey and impact of losing a loved one unexpectedly. And like with Roethke, I can tell it is artful. And I can see the characters developed fully and responding in ways that I recognize. But something just beyond me is there, which is an openness of feeling.

I wanted to love this book. I began it expecting to do so, almost prematurely praising its magnificence. And I liked it greatly. However, I wanted to love it a little more than I actually did. I hope to one day return to it and find myself awash in the feelings Agee bares. For now, though, I still admire his prose poetry. Like this:

"How still we see thee lie. Yes, and between the treetops; the pale scrolls and porches and dark windows of the homes drifting past their slow walking, and not a light in any home, and so for miles, in every street of home and business; above thy deep and dreamless sleep, the silent stars go by.

He helped his mother from the curb; this slow and irregular rattling of their little feet.

The stars are tired by now. Night’s nearly over.

He helped her to the opposite curb.

Upon their faces the air was so marvelously pure, aloof and tender; and the silence of the late night in the city, and the stars, were secret and majestic beyond the wonder of the deepest country. Little houses, bigger ones, scrolled and capacious porches, dark windows, leaves of trees already rich with May, homes of rooms which chambered sleep as honey is cherished, drifted past their slow walking and were left behind, and not a light in any home. Along Laurel Avenue it was still darker. The lamp behind them no longer cast their shadows; in the light of the lamp ahead, a small and distant bit of pavement looked scalded with emptiness, a few leaves were touched to acid flame, the spindles and turned posts of one porch were rigidly white. Helping his mother along through the darkness, Andrew was walking much more slowly than he was used to walking, and all these things entered him calmly and thoroughly. Full as his heart was, he found that he was involved at least as deeply in the loveliness and unconcern of the spring night, as in the death. It’s as if I didn’t even care, he reflected, but he didn’t mind. He knew he cared; he felt gratitude towards the night and towards the city he ordinarily cared little for. How still we see thee lie, he heard his mind say. He said the words over, drily within himself, and heard the melody; a child’s voice, his own, sang it in his mind."

I appreciate that even in a book about the grief that overwhelms those bereft at the loss of their companion, a character as numb as I can be is still given such beautiful words in treatment. It's a lovely book. Read it and be better for it.

Good night.

I don't understand this book yet. But this is because I don't understand life yet. There is so much Clarissa Dalloway in these 190-some pages, and so much of many of us in Clarissa Dalloway. I expect to learn from her in rereadings throughout the years.

I don't understand this book yet. But this is because I don't understand life yet. There is so much Clarissa Dalloway in these 190-some pages, and so much of many of us in Clarissa Dalloway. I expect to learn from her in rereadings throughout the years.From the day's first task of buying flowers, we are taken through the experience of a day as a microcosm of the daily grind of life, that which we relive each day and during which we relive the totality of our lives. While Mrs. Dalloway's inner thoughts and associations are played out, those of other players she encounters are revealed as well, though these experiences never intersect. We see how different the impressions of events and people appear to different characters, and also that these misconclusions will largely never be reconciled. To describe the book in this way is to be reductionist, though. It is about much more than simple misunderstandings, yet at its center are the pains caused by inabilities of characters to truly understand each other.

I didn't expect to be drawn in by Woolf's flowery writing and meandering, introspective subject matter. I found much to recommend her, though. I don't know that I'm thrilled that her style and subject matter have been so influential on the past century's writing so as to glut the market with so-called "literary fiction" that is more style than substance; but because Woolf's writing is at least equaled in substance to its impeccable writing style, she is more than worth the read.

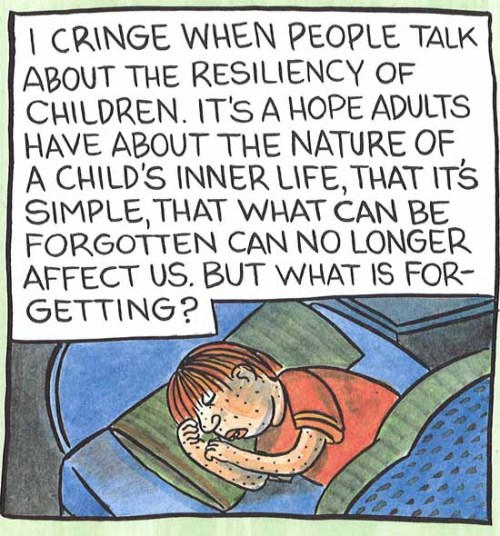

ONE HUNDRED DEMONS!!!!!!!

ONE HUNDRED DEMONS!!!!!!!

Some of the demons are things she can't remember. Other times, they're things that won't go away.

In a mixture of collage and totally uniquely styled comics, Lynda Barry tells some of the stories that have shaped her life in a relatable, funny, original, and engaging way. And I just love the way the book is shaped, easy to hold in your hands while feeling very substantial, too. She belongs to the small selection of comics and graphic novelists who I plan to read exhaustively; Alan Moore, Alison Bechdel, Calvin and Hobbes, and Kate Beaton are there, too.

I aint no infidel. Dont pay no mind to what they say.

I aint no infidel. Dont pay no mind to what they say.No.

I always figured they was a God.

Yes.

I just never did like him.

This is a world of Biblical proportions and ancient language; prose that tumbles, lurches, and forks like tributaries of the river where Suttree makes his home, shot through with a sense of universal wonder as well as doom. Much of what we see is either hollow or empty or different than it first appears. It is a book about the things, both human and inanimate, that we throw away, and what happens to everything that floats along and begins to decay or ferment in utter disregard and abandonment. A flotsam-and-jetsam-eyed view of the world, dirty and messy and ugly, but then surprisingly beautiful and touching, too. It is all the things that make up the world. This world and this man are either tumbling toward utter destruction or just about to be reborn; are these the same thing?

They was nine of us you know. Me and Elizabeth outlived all the boys and now she's gone and I'm in the crazy house. Sometimes I don't know what people's lives are for.

In many ways, the story resembles a river. It is often familiar, describing the same kinds of scenes many times; the way the city's lights reflect off of the river or the color of the grime on a bum's hands. But then we remember both that these are the daily images of Suttree's life and that a river often looks the same each day and at many places along its stretch, but in fact is never the same place twice, being constantly in a state of flow. These characters are in flux as well. Carnivalesque in all its fluctuating impermanence. The cast our hero meets resemble the squatting inhabitants in Steinbeck's [b:Cannery Row|4799|Cannery Row (Cannery Row Series, #1)|John Steinbeck|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1309212378s/4799.jpg|824028] or [b:Tortilla Flat|163977|Tortilla Flat|John Steinbeck|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1347567359s/163977.jpg|890203], with Suttree playing the parts of voice-of-reason and reluctant compatriot when not abjuring aloofly. We see the seasons change and feel the rhythms of the land. But most of all, we are engrossed with a sense that if there is a God, he has abandoned this place or these people, and there is little they can do but try to find their own ways.

He said that even the damned in hell have the community of their suffering and he thought that he’d guessed out likewise for the living a nominal grief like a grange from which disaster and ruin are proportioned by laws of equity too subtle for divining.

It is beautiful. It is horrific. It is utterly worthwhile. Maybe.

He looked at a world of incredible loveliness. Old distaff Celt's blood in some back chamber of his brain moved him to discourse with the birches, with the oaks. A cool green fire kept breaking in the woods and he could hear the footsteps of the dead. Everything had fallen from him. He scarce could tell where his being ended or the world began nor did he care. He lay on his back in the gravel, the earth's core sucking his bones, a moment's giddy vertigo with this illusion of falling outward through blue and windy space, over the offside of the planet, hurtling through the high thin cirrus.

Suttree was certainly the most rewarding book I read this year, in calculations of effort to understand compared with value received. It won't be the last McCarthy work I tackle. He gets at something deep and primal within his characters and I can't wait to read more.

There's plenty that could be said in praise of this book. The innate code of honor that rules the characters echoes (albeit more starkly) heartland poet Bruce Spingsteen's "Highway Patrolman":

There's plenty that could be said in praise of this book. The innate code of honor that rules the characters echoes (albeit more starkly) heartland poet Bruce Spingsteen's "Highway Patrolman":Me and Franky laughin' and drinkin' nothin' feels better than blood on blood

Takin' turns dancin' with Maria as the band played "Night of the Johnstown Flood"

I catch him when he's strayin' like any brother would

Man turns his back on his family well he just ain't no good

Author Daniel Woodrell's prose is spare but rich, memorable particularly in his use of active metaphor:

Fading light buttered the ridges until shadows licked them clean and they were lost to nightfall.

Most remarkable and notable to me in all this was the way that the characters were drawn in connection to the Ozark country, sculpted out of its mud like Adam and Eve or out of its brush like Ask and Embla. It's not just a backdrop or a even home; these hills are what these Dollys are made of. Early on, this description of heroine Ree Dolly's mad mother is grabbing:

"...you could see she'd once been as comely as any girl that ever danced barefoot across this tangled country of Ozark hills and hollers. Long, dark, and lovely she had been, in those days before her mind broke and the parts scattered and she let them go."

Gone to the wind, among those caves that Ree takes up in for shelter on a trek to save her family from the Law, I imagined. The landscape shapes their loyalties, the bonds of extended family not being strong enough to bridge the alliances limited not just to state, region, or county but to a single valley. The Bromont-Dolly family's one legal resource, their old-growth timber acres, is off limits because it is rooted to who they are:

"...all the old-growth timber was much coveted by sneaking men with saws. If sold, the timber could fetch a fair pile of dollars, probably, but it was understood by the first Bromont and passed down to the rest that the true price of such a sale would be the ruination of home..."

As Ree struggles with challenges above the carrying capacity of many of us, and certainly a sixteen-year-old, her inner processes often take her away physically, fantasizing about an ocean far away, while likening stresses to the more familiar "crumbling away inside like mud banks along a flood stream". By the end, having survived, Ree no longer plans to flee to the army and "places we wouldn't be" as brother Harold puts it; she finds beauty in the winter instead of agony. But if her last words are any indication, they may not be there forever.

I can't help but see something biographical in this human-land connection that Woodrell builds. He grew up in the Ozarks and through the Marines and college, spent many years away. But then he returned. Does he want Ree to skip the middle-time? And is he writing this story for people like her, or for the people he met when he went away, to explain why he had to go back?

I started reading these books in high school in an attempt to understand the 'normal' girl. They helped. They also made me glad I wasn't.

I started reading these books in high school in an attempt to understand the 'normal' girl. They helped. They also made me glad I wasn't.

I was in love with the person who recommended me this book. And so when I realized that it was a book largely about a character obsessively in the throes of the first great love of his life, the experience of reading it began to resemble drunkenly meandering through a maze that became a hall of mirrors. I had to stop about 1/3 through and return six months later because of the rawness of the characters' experiences.

I was in love with the person who recommended me this book. And so when I realized that it was a book largely about a character obsessively in the throes of the first great love of his life, the experience of reading it began to resemble drunkenly meandering through a maze that became a hall of mirrors. I had to stop about 1/3 through and return six months later because of the rawness of the characters' experiences.In the same way that it can be hard to articulate exactly what makes you love a person, the same is often true about the books I love most. They contain something ineffable, something beyond the sum of their parts. What I can say is that Maugham is writing out of his soul here and baring it to the world in black and white ink. And he's doing it while being remarkably insightful and expressive, drawing characters whose inner landscapes are as richly described as Steinbeck might rhapsodize about the Salinas Valley. As Philip moves through different cities, classes, and acquaintances, each person illuminates some new understanding about the world. That this bildungsroman is structured with its main character coming to understand the world by observing his reflection in the people (and books) around him is unique among the coming-of-age stories I've read. Often the conceit seems to be that maturity is developed through the character reacting and changing in response to an unusually trying crisis, and he learns the lessons either in isolation or at the feet of a particular sage. Philip's path is more recognizable to me, and seeing him go through it provided a reciprocal learning experience.

The outstanding question that I will revisit when I reread this book sometime later is whether Maugham's thesis is true: is Philip doomed to either endure the agony of either unrequited love or the pallidness of mere affection? Regardless of the answer to this question, it is a story excellently told, masterfully drawn, and rich in genuine feeling.

My introduction to Frank O'Connor came through his famous short story "Guests of a Nation". Some stranger on the internet said I should read it, and I was astonished. Such rich language, humor, empathy, outrage, and, in the end, sorrow. Surely one of the most devastating endings in the history of short stories.

My introduction to Frank O'Connor came through his famous short story "Guests of a Nation". Some stranger on the internet said I should read it, and I was astonished. Such rich language, humor, empathy, outrage, and, in the end, sorrow. Surely one of the most devastating endings in the history of short stories. I immediately had to find more of his works, and my local Half Price Books store had a copy of this volume, authoritatively titled The Best of Frank O'Connor. There are a few other collections of his works in varying stages of being in print and being more or less comprehensive, and I can't speak to their qualities. The great thing about this book, though, is that it doesn't just package all his short stories without context; it includes letters, essays, reviews, and other pieces of his writings thematically placed among the stories to give insight into his influences and thought processes. It makes it all the more interesting to spend some time sifting through his work. Truly a rewarding experience.

Wonder Boys

This is a flawed, imperfect book and yet I give it five stars. It earns the stars partly because its own imperfections are consistent with the celebration of humanly flaws throughout the novel, and partly because its digressions, occasionally odd word choice, flailing subplots, and third-act inconsistencies don't detract from the strong, original voice and full-bodied characters. It's also remarkably hilarious. And "true".

This is a flawed, imperfect book and yet I give it five stars. It earns the stars partly because its own imperfections are consistent with the celebration of humanly flaws throughout the novel, and partly because its digressions, occasionally odd word choice, flailing subplots, and third-act inconsistencies don't detract from the strong, original voice and full-bodied characters. It's also remarkably hilarious. And "true".Fundamentally, what most impacted me about this book was how powerfully it convinced me to not read so much, goddammit! Especially for a book whose characters are consumed with a passion for the written word. The haze in which the main character Grady Tripp goes about his daily life, and the description of his student James' great first novel ('It was a fiction produced by someone who knew only fictions'), both contribute to dethroning the majesty of literature. The movie is a masterful adaptation, and it adds some moments of brilliance that are absent from the novel, but it doesn't come close to the conviction, more convincingly expressed here than in anything else I've read, that life is meant to be *lived*. And, like I said before, it's absolutely hysterical at times.

The remarkable thing about this book is how quiet it is. When reading it during a fairly stressful time in my young life, this book had a palpably calming effect, like the words washed over my troubled mind with their effortless grace. The imagery was memorable, the concern for home-making timely, but most notable was its simplicity. I imagine that if you threw this book into a lake, it would dive without the slightest splash and a minimum of ripples, in spite of its light weight. Sometimes it's just the thing a person needs to clear her head.

The remarkable thing about this book is how quiet it is. When reading it during a fairly stressful time in my young life, this book had a palpably calming effect, like the words washed over my troubled mind with their effortless grace. The imagery was memorable, the concern for home-making timely, but most notable was its simplicity. I imagine that if you threw this book into a lake, it would dive without the slightest splash and a minimum of ripples, in spite of its light weight. Sometimes it's just the thing a person needs to clear her head.